14 minutes

#03 – Debt and Hangover

- Should You Read It?

- What Is Credit?

- Credit Hangover

- Credit and Interest Rates

- Inherent Fragility

- What Happens After The Hangover?

- Final Thoughts

- Dig Deeper

- Highlights for The Curious

So I just read Navigating Big Debt Crises by Ray Dalio. This book fell into my hand because of my interest in big systemic society changes. I put it into the category “I want to understand how the world works”. Ray Dalio did a great work, the book is easy to read and to understand.

Should You Read It?

If you are interested in learning about large systemic changes that potentially mean the ruin of millions of people, this book is for you. It is about credit and debt and how they are embedded in society. Just like alcohol or lack of sleep, a bit of it is “ok” but get used to it and you slowly implode.

100% guarantee.

Let’s start with the basics.

What Is Credit?

Credit is buying power in the present and less buying power in the future.

Imagine you and I are in the desert. We are thirsty and one hour away from the oasis. You ask me a bottle of water and promise to give it back when we reach safety. You have water in the present (credit) and less water in the future (debt).

We need a lot of water - Source

Credit is helpful. You survived and we reached the oasis. But debt is always paid.

If you give me the water back at the oasis, debt is paid.

If you don’t give me the water back because you died on the way (yeah I’m sorry), debt is gone. When I dreamed about all the water I had, I counted the bottle you owed me. Since the water has disappeared I have to subtract one bottle of water from my calculations. In a sense I paid the debt for you: you got free water instead of some water now and less water in the future because I miss one bottle of water.

The moment water was given also created a moment in the future where there would be less water in the future for you or me. This is why debt is always paid.

Credit is a buffer that allows humans to explore an unknown future using resources they don’t have in the present. If in the future they can bring back more resources, there is growth. If not, there is pain because some have to sacrifice their resources to pay back. The alternative to credit would be to have less buying power in the present (saving resources) in order to have more buying power in the future.

Credit is a way for societies to expand and grow. Credit also means risk because it deals with an unknown future. Easy right?

So we have our small example of credit and debt with water but what happens when we apply this dynamic to a society ? Spoiler alert: big debt crises.

Credit Hangover

When credit is available and cheap (much buying power in the present), people buy assets and prices rise. If everyone has plenty of money to buy houses, houses prices rise. People feel richer because their assets rise in value. Everyone is happy, things are great.

However this leads to a self-reinforcing loop: assets prices rise, everyone is richer, people get even more credit because they are trustworthy (they’re rich after all), they buy more assets, prices rise again. Rinse and repeat a few times and we have a bubble.

However the more credit is used to inflate prices, the more the debt burden rises: debtors have more and more less buying power in the future. And remember, debt is always paid. At some point in the future, debtors can not live with their decrease in buying power and have to sell their assets to cover the debt burden.

The first to sell are lucky. The second as well because prices are still high. Unfortunately for the others, the more the sell pressure increases, the lower the prices fall and the faster the wealth shrinks while the debt burden remains. Ultimately, the trend fully reverses and everyone needs to sell to cover their debt burden. Banks have less money (they also own depreciating assets). There is less credit available and the economy contracts. No one has buying power anymore. We have a crash.

And voila, you have a big debt crisis. The society who was over-leveraged is now facing a deleveraging. In that case it is a deflationary deleveraging which means prices are falling. In that scenario, you fare better holding cash than assets because cash will increase in value while assets depreciate.

deleveraging: the process of reducing debt burdens

This was a very broad template of a big debt crisis. However I think it is misleading to call it a “debt crisis”. When someones drinks shots of vodka all night and has an hangover the next morning, we don’t call that an “alcohol crisis”. Too much alcohol leads to an hangover and too much credit leads to a crash.

If debt is not hard reset from time to time, debt is piled over debt. The longer the time between the reset, the harder the hangover. So how is that managed in practice ?

Credit and Interest Rates

Imagine a country. In this country there is a central bank. This central bank sets the interest rate on the credit. This interest rate is basically the cost of credit. How so ?

When you and I exchanged one bottle of water, there was an interest rate of zero. If the interest rate had been X%, the situation would have been: “You will give me back one full bottle of water plus one filled at X% when we’re at the oasis”. The higher interest rate, the higher the cost of credit: you have to pay more in the future for the same buying power in the present.

When the central bank decides there is too much credit in circulation and bubbles start appearing, they can dry the source of credit by raising the interest rates. Credit becomes more expensive. People have less buying power and higher credit burdens to cover. This sets in a deflationary process: everyone has to sell to cover their now higher burdens. Raising interest rates is a tool for central banks to fight inflation and bubbles.

On the opposite, when the economy halts because there is no credit available and no money is circulating, the central banks can turn on the source of credit by lowering the interest rates. People have access to cheaper credit, they can buy things with leverage again and the economy is bootstrapped.

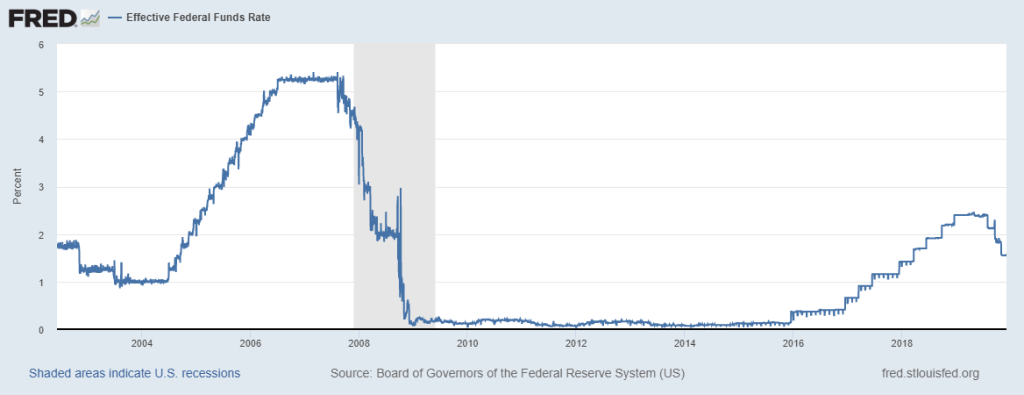

For example, see how the Federal Reserve lowered the interest rates after the financial crisis of 2008 in order to restart the economy. This among other levers used by governments is frequently observed after depressions. The book goes in a lot more detail about dozens of past crises if you’re interested (1922, 1929, 2008 etc.)

The Fed lowered the interest rate close to zero in 2009 for several years to restart the economy - Source

So why the crisis since we can manipulate credit ?

Inherent Fragility

Fragility means that over time the studied object will break. The problem is that the system the central bank is managing is inherently unstable and fragile. Let’s dig.

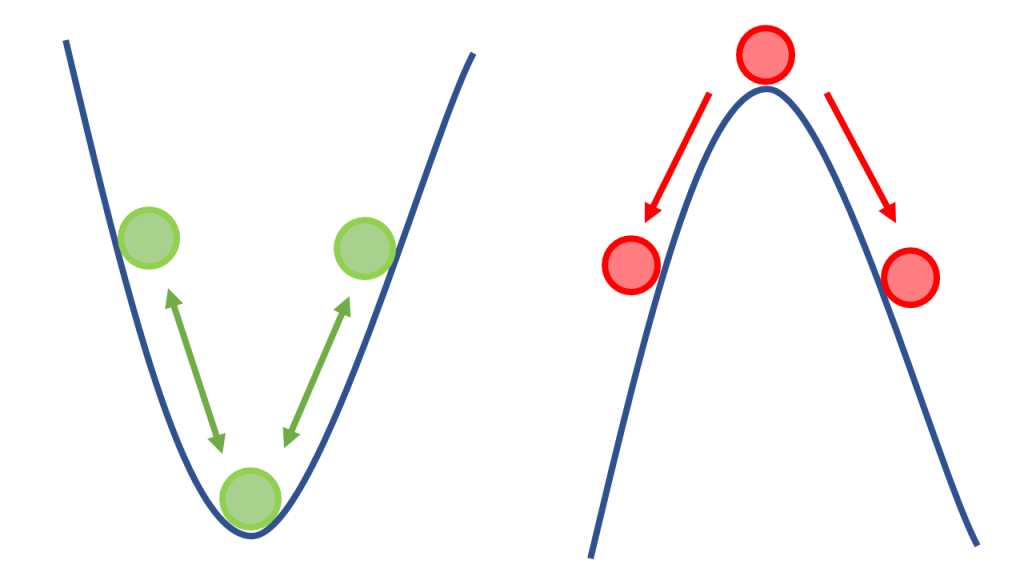

A stable system is a system where a small deviation leads to the same state of equilibrium (green circle below). An unstable system is a system where a small deviaton leads to another equilibrium. The new equilibrium may be far away and the transition may be fast and explosive (red below).

Green state at the bottom is stable. Red state is unstable: a small deviation leads to a new state of equilibrium.

Green state at the bottom is stable. Red state is unstable: a small deviation leads to a new state of equilibrium.

Being in charge of the interest rate is a bit like being the red circle:

- when there is too much credit, we have inflation and bubbles

- when there is not enough credit, we have deflation and crashes

Credit must therefore be managed with utmost precision. Unfortunately, there is no way to intellectually apprehend all the complexity of a whole country’s economy. It gets even worse when this country is tied to other countries with each its own central bank. It gets even worse when the feedback loops are super long: how do you assess the effectiveness of your decisions when it takes years to see the effects and when there are so much variables involved ?

You get it. Adequate management of the credit cycle by central banks is a pipe dream. This is not to say they are bad at their work or ill-intentioned. The task is just beyond realistic. Hangovers are inevitable with the current system.

What Happens After The Hangover?

When lenders lose the money they thought they had because debtors default, debt starts getting paid because those lenders write down losses. Remember when you did not give me my water back, I lost one bottle. Ultimately if all the losses were written down, debt would be paid.

However if the lenders (= the banks) are losing too much they risk being insolvent. Since other people are relying heavily on those lenders, the lenders can not go insolvent. Those people are for example you and me: we lend money to the banks in the form of our bank accounts. We expect to have our money back. (Note that this is simplified: in reality everything is super intricate and everyone lends to everyone.)

Those banks who can not go insolvent are “too big too fail” which means the system, which looks very much like a house of cards, collapse if those lenders fail.

The government is in a trap at this point and the only way out is to bail them out or face total economic collapse. That means buying their debt by monetizing it. If bank A is missing Y billions, the government can raise more debt and provide Y billions printed out of thin air by the central bank to bank A. At that point debt is paid, not by the lenders or the creditors but by the society at large.

However, this is not a fix since after all the debt is paid, we start a new cycle. Moreover, having to pay the debt the government has to cut in its spending: less schools, hospitals, social support, etc. This leads to unrest in the population and gives space to populist leaders across the world.

We are currently in such a cycle: lot of cheap credit is available and interest rates are low. Asset prices are inflated. The interest rates can’t be raised much because it would crash the economy. When the debt burden will become too high and the first signs of a recession will appear, the interest rates will have to go lower to provide more cheap credit and buying power to keep the machine running.

Once the interest rates hit zero like in Europe, the next step is negative interest rates ( Switzerland, Sweden, Japan) [source].

Who will accept to have less money in the future after putting money in a saving account for years ? How will society at large react ? Will people pull their money out of the banks ? I don’t know.

What I do think I know though is that we can’t have debt fueled economy and indefinite growth without a pullback.

Final Thoughts

I was a child during the last financial crisis as well as a lot of people who did not live it fully as well. This is why it is particularly important to learn history. Those who ignore past mistakes will lose time, energy and resources doing those same mistakes again. We have to go beyond What You See Is All There Is.

However knowing the past is not a safeguard for the future because in hindsight everything always seems obvious while it was not at the time.

This is where we are now: we have no idea where we are going but in 5 years we’ll look back and say “Yeah, makes sense”.

Trying to understand debt and money is hard. Knowing how fundamental money is in our society as a basic language to transmit value, I find it highly disturbing. It should be basic knowledge but it is not. I think this gap between this fundamental tool and our understanding of it weakens us as a society. I hope I helped to bridge that gap a little bit even though there are still some obscure areas.

Dear reader, I highly value your time so thank you very much for having read this article.

Have a beautiful end of the day.

Dig Deeper

- How the economic machine works in 30 minutes ?

- The Coming Retirement Crisis Explained and Explored (w/ Raoul Pal)

- A blog about the US economy

Highlights for The Curious

Experts predictions

On Monday, March 9 (2009)

(…) the World Bank came out with a very pessimistic report and Warren Buffett said that the economy had “fallen off a cliff.” The stock market fell by 1 percent. Investor sentiment was extremely bearish and selling was exhausted. That was the day the bottom in the US stock market and the top in the dollar were made, though it was impossible to know that at the time._

At the start of 1929, The Wall Street Journal described the pervasive strength of the US economy: “One cannot recall when a new year was ushered in with business conditions sounder than they are today… Everything points to full production of industry and record-breaking traffic for railroads.”

Ray’s definition of a bubble

- Prices are high relative to traditional measures

- Prices are discounting future rapid price appreciation from these high levels

- There is broad bullish sentiment

- Purchases are being financed by high leverage

- Buyers have made exceptionally extended forward purchases (e.g., built inventory, contracted forward purchases, etc.) to speculate or protect themselves against future price gains

- New buyers (i.e., those who weren’t previously in the market) have entered the market

- Stimulative monetary policy helps inflate the bubble, and tight policy contributes to its popping

The importance of history

(…) What happened was the same as what happened in 1933, and for the same reasons, but I hadn’t studied what happened in 1933, so I was painfully wrong. That was the first time that I was surprised by events that hadn’t happened in my lifetime but had happened many times in history. (…). The events I am describing to you that happened in the 1930s have happened many times before for the exact same reasons._

Austerity never worked

(…) all of the deleveragings that we have studied (which is most of those that occurred over the last couple of hundred years) eventually led to big waves of money creation, fiscal deficits and currency devaluations (against gold, commodities, and stocks).

About bailing out

(…) Geithner told me that the interesting thing about this approach was that instead of losing 5 to 10 percent of GDP on the cost of the financial rescue, we actually earned something like 2 percent of GDP, depending on how you measure it. That’s a dramatic outlier in the history of financial crises, and Geithner credits it to the Fed and Treasury’s very aggressive response and their willingness to put moral hazard concerns aside. I agree.

Monetization of debt

Think of it this way: There are only goods and services. Financial assets are claims on them. In other words, holders of investments/assets (i.e., investors/capitalists) believe that they can convert their holdings into purchasing power to get goods and services.

At the same time, workers expect to be able to exchange a unit’s worth of their contribution to the production of goods and services into buying power for goods and services.

But since debt/money/currency have no intrinsic value, the claims on them are greater than the value of what they are supposed to be able to buy, so they have to be devalued or restructured.

In other words, when there are too many debt liabilities/assets, they either have to be reduced via debt restructurings or monetized. Policy makers tend to use monetization at this stage primarily because it is stimulative rather than contractionary. But monetization simply swaps one IOU (debt) for another (newly printed money). The situation is analogous to a Ponzi scheme. Since there aren’t enough goods and services likely to be produced to back up all the IOUs, there’s a worry that people may not be willing to work in return for IOUs forever.